American Born Chinese

Gene Luen Yang

Published in 2006 by First Second

The Story: The graphic novel American Born Chinese tells three seemingly unconnected tales:

- Jin Wang’s family moves from San Francisco’s Chinatown to a new neighbourhood, and Jin finds he’s one of the only Chinese-American students at his school. He and his other Chinese friends are picked on constantly, and to make things even worse, Jin falls in love with a stereotypical All-American, blonde haired, blued eye girl in his class.

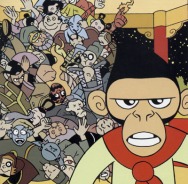

- The Monkey King was born from a rock, and soon after establishes his monkey kingdom. He’s mastered the Arts of Kung-Fu, the Four Major Disciplines of Invulnerability, and has achieved the Four Major Disciplines of Bodily Form. However, even with power and adoring subjects, the gods, goddesses, demons and spirits of heaven only see the Monkey King as . . . a Monkey. The Monkey King yearns for the respect he deserves.

- Chin-Kee is the accumulation of every negative Chinese stereotype. Once a year he visits his cousin Danny in America and RUINS HIS LIFE. After every visit Danny has to transfer to a new school to escape the ridicule his cousin brings. This year’s visit is worse than ever.

What Wallace and I Think: A review on the back cover of my edition compares American Born Chinese with Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye (a wonderful comparison in my opinion) in that they both explore “the impact of the American Dream on those outside the dominant culture” (School Library Journal). This is a story as old as the American Dream itself, but with the current success of ABC’s sitcom Fresh Off the Boat, nearly ten years after it was first published American Born Chinese’s continues to be significant. Yang’s graphic novel tackles stereotypes, as well as the effects these stereotypes have on first-generation Chinese-American children. At its core, the graphic novel is a coming of age story for Jin who must learn to integrate himself in American culture while also maintaining his Chinese roots. Because of the constant teasing and racist assumptions Jin’s peers make, Jin thinks the only way to be accepted into American society is to erase his “Chineseness”. But, as a wise woman tells a young Jin (after learning he wants to be a Transformer when he grows up), “It’s easy to become anything you wish . . . so long as you’re willing to forfeit your soul” (29). What Jin must determine is whether forfeiting his soul to become what he thinks he wants is worth the price.

The Monkey King’s story is a delight and a gateway to further exploration of Chinese fables. The Monkey King is tied into Jin’s story-line in a surprising way, and also introducing readers to a traditional Chinese story. The Monkey King is a main character is the Chinese Classical novel Journey to the West, and is also found in later stories and adaptations. The Monkey King’s section loosely follows the story line of Journey to the West. Like the classical novel, Yang’s Monkey King is imprisoned under a mountain after rebelling against heaven, and is only released from the mountain when he agrees to accompany a Monk, Xuanzang (who also appears in the graphic novel), on a journey. Yang updates the fable, for the Monkey King’s mission intersects with the story lines of Jin and Chin-Kee. Comparing the Monkey King’s protrayal in American Born Chinese to his classical protrayals could make for interesting discussions.

Chin-Kee’s story line should make you feel uncomfortable. Blatantly a racist depiction of Chinese stereotypes, Chin-Kee forces American-Chinese characters to confront fears of how they’re being perceived. Chin-Kee is the conscience of the graphic novel and acts as a “signpost” to Jin’s “Soul” (221). He also acts as the signpost and conscience of readers who may be to blame for acting similar to Jin and Danny’s bullies in the graphic novels; to those who are to blame for naming the stereotypes and bringing them into being. Mary Roche argues a main benefit of reading literature is that it opens us up to the lived experience of others, deepening our sympathies and understanding beyond our own lived experience. Given the chance, this is what American Born Chinese can accomplish, especially through the depiction of Chin-Kee and how he links up to the two other story lines. And to those that already identify with Jin’s experience, the graphic novel functions as a friend, who will warmly put his arm around your shoulder and say “you are not alone. You matter.”

This is a young adult graphic novel, and I would recommend it to grade seven readers at the youngest.

I give this novel a 5/5